Prior to this year’s DH conference in Montreal, Canada (8 – 11 August) some of us flew in a little earlier to come together for a workshop in the context of the 3DH project. Apart from the core project team and our colleagues Evelyn Gius and Marco Petris we were joined by our associated members Johanna Drucker, Geoffrey Rockwell and Marian Dörk as well as Laura Mandell.

Over the span of two and a half days we had an intense and productive workshop that had the goal of refining and reifying the three concepts we had developed so far over the course of the last weeks. Springboards for this process were on the one hand our four conceptual 3DH postulates: 2-way-screen, parallax, qualitative and discursive, on the other hand reflections about supporting the process of interpretation in digital tools. We specifically discussed the relevance of the article “Thinking about interpretation: Pliny and scholarship in the humanities” by John Bradley.

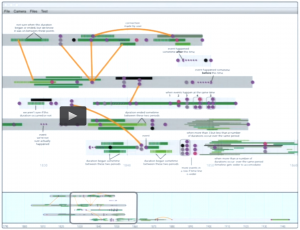

What is intriguing in the software “Pliny” described by Bradley, is, that scholars are very not bound in the way they organize their notes and annotations, there is no need to assign distinct categories or relations to them. Instead, these can be organized on a plane and emerging structures becoming apparent can be inscribed by encapsulating them in boxes, when the interpretation progresses.

This appears to be a way of modelling interpretative data that takes into consideration methods scholars have been using in the analog world, however, also exceeds that and opens up new possibilities enabled by the digital (in terms of interaction with and visualization of data), an approach that seems very much related to the goals of the 3DH project as well.

In our design process so far we have based our concepts on real-world scenarios fed by experiences of literature scholars in research projects and arrived at similar conclusions as Bradley: It seems counterintuitive for scholars to force them to apply structure to their annotations when they start with their process. Relations between and qualitative statements about annotations often can only be made when the process has progressed.

When we discussed the wireframes in the workshop we realized that we can differentiate two different environments or spaces of literary scholarly work: Johanna called this research and argument space. While we define typical descriptive acts of the scholarly process like annotating, collecting and commenting as research activities, we consider tasks like grouping, ordering and organizing as interpretative or at later stages argumentative activities. Usually scholars switch between activities of either of the modes perpetually.

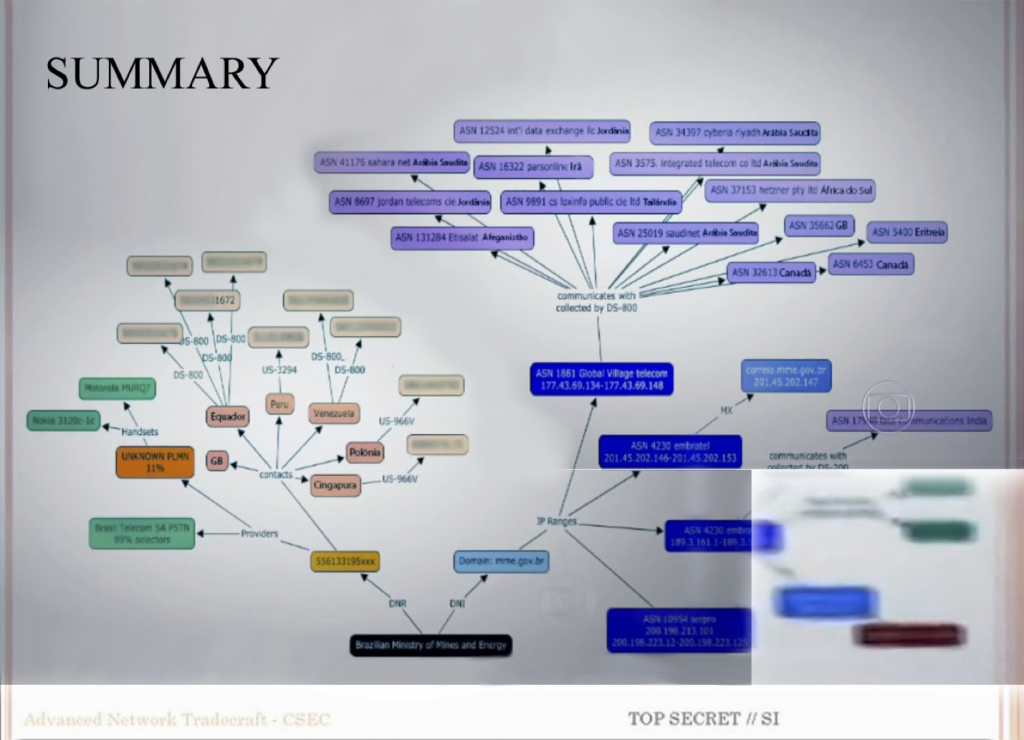

Interplay between research environment and argument environment (by Johanna Drucker)

Interplay between research environment and argument environment (by Johanna Drucker)

We understood that this circumstance has to be supported by the interface much more deliberately. Thus, for the next steps in the design process we will focus on the representation of and interaction between these spaces in the interface. What would an interface look like that supports continuous switching between these mentioned activities?

In the discussion we came up with the concept of a semantic plane that might allow us to bring these two spaces together. While we would produce annotations in the research phase that would be represented as glyphs on the plane, in the argument phase we would position and manipulate these glyphs to assign meaning to them and create arguments that we later can publish.