It’s about time for a new blog post! 3DH has progressed quite a bit in the last couple of months. We fleshed out wireframes based on the conceptual foundations that came out of the workshop in Montreal, iteratively refined them and finally brought the concept to an interactive prototype level that we were able to present at the DHd2018 conference in Cologne.

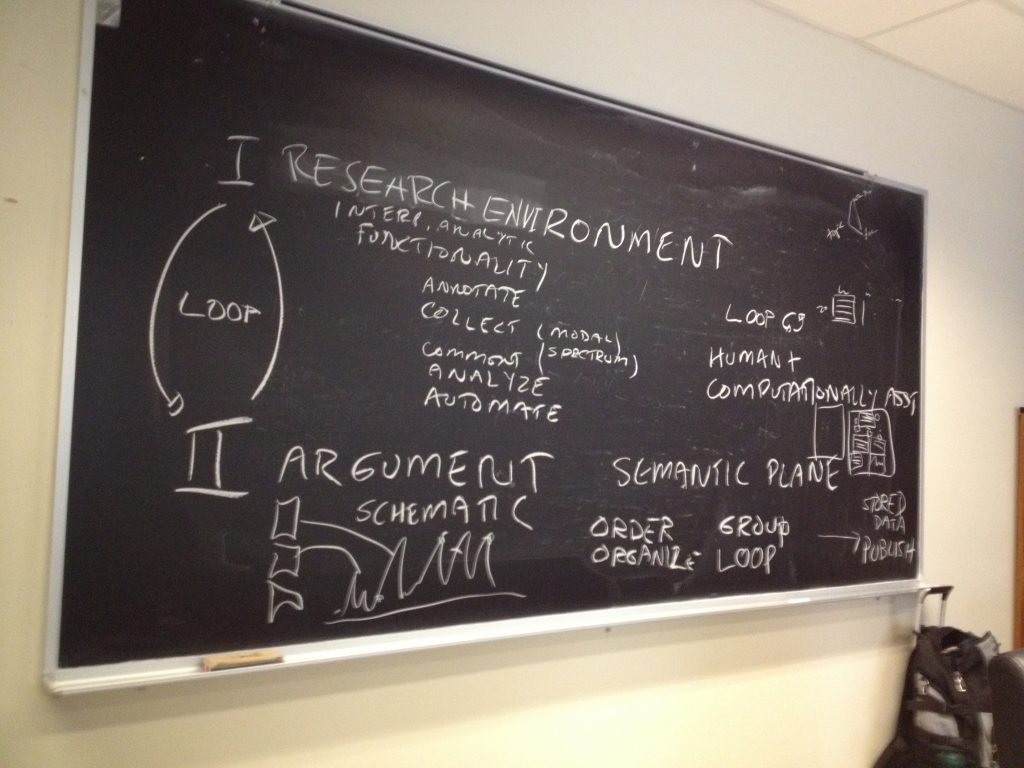

After the Montreal workshop we focussed on the classic close reading scenario with an emphasis on interpretation because it can be considered the one to which 3DH postulates apply the most, so we wanted to make sure we cover that first: Exploration of free annotations to sharpen the literary research question.

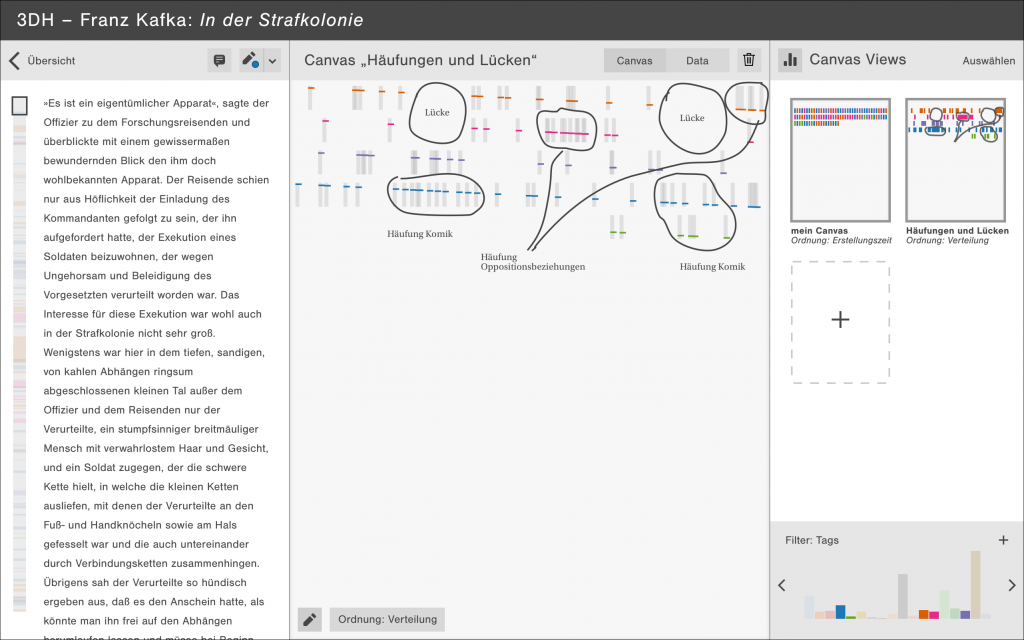

Developing an early prototype as a proof-of-concept for this scenario first would make it easier to transfer interface principles to the other scenarios, so we reasoned. Over the course of the last months we chose a text we deemed appropriate for the prototype and for the intended audience and populated the scenario with real data. The text we wanted to annotate needed to fulfill some basic requirements: It should be well-known, so people can relate to it. It should be complex enough, so different paths of interpretation can be pursued and it should be short enough, so people can actually read the text without spending too much time, if they want to. It should also be long enough, so visualization as a method of getting an overview really makes sense. We picked the short story In der Strafkolonie von Franz Kafka.

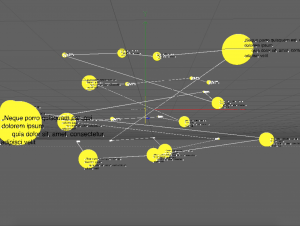

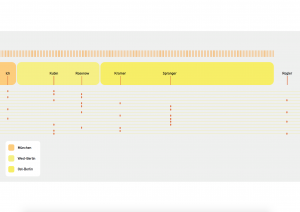

For this short story we created over 600 annotations in 19 different interpretation categories in Catma. In the next step we exported our Catma annotations as JSON and built a web-based demonstrator with Javascript and D3 that shows the most important interactions of the concept.

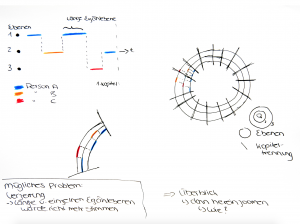

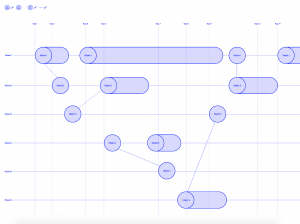

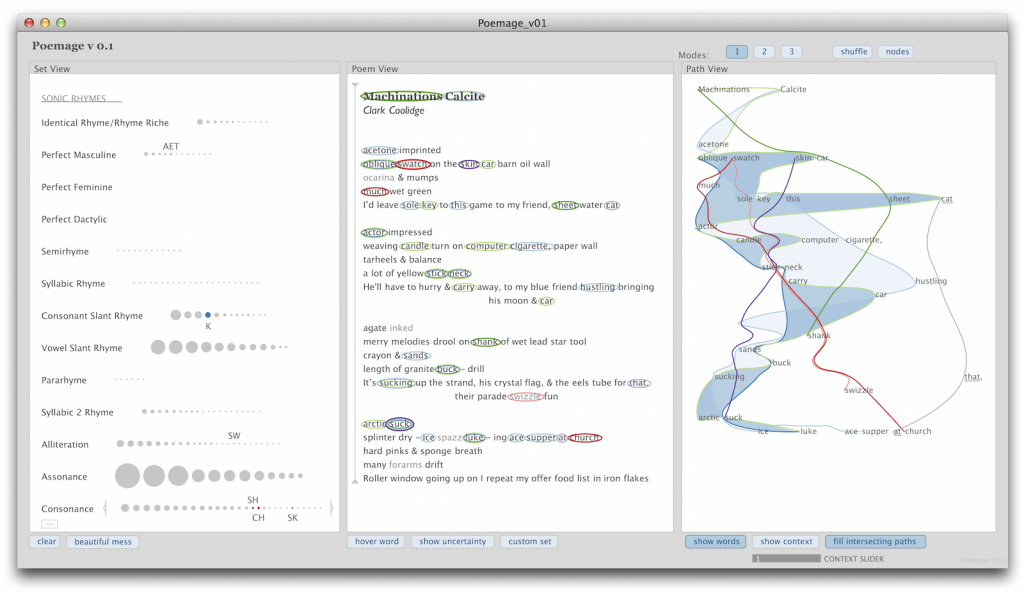

The main principles of our concept are the tripartition of the interface and the representation of annotations as glyphs. So, while we clung to the idea of glyphs (mentioned in the last article), we have abandoned the idea of a strict spatial separation between the two activity complexes research and argument. We came to the conclusion that scholarly activity is better represented by three adjustable spaces text, canvas and argument.

Here text is simply the part of the interface, where our research text can be read and annotated. For each annotation a glyph is created on the canvas in the middle of the interface. We can sort these glyphs, structure them according to different criteria and draw connections between individual or groups of glyphs. Scholars can save multiple canvasses each of them highlighting a particular aspect of the text. In the argument space on the right side of the interface these canvasses can be combined and arranged to form an argument.

Since this year’s topic of the DHd2018 conference was critical perspectives on digital humanities, our contribution put an emphasis on our design process and the accompanying design-based critical perspective we have applied in the process. We talked about how we incorporated the four methods scenarios, wireframes, prototyping and design reviews into our process and how these helped us to gain new insights and arrive at the current state of design.

Here’s a link to the early prototype that allows you to explore the interaction between annotations and glyphs:

You can find our slides here:

These two videos show the interplay between the three parts of the interface:

Interplay between research environment and argument environment (by Johanna Drucker)

Interplay between research environment and argument environment (by Johanna Drucker)